Your cart is currently empty!

origin

all our Japanese teas are grown and hand-made by a small tea farmer in Onomichi, Japan

the japanese tea room ‘cha-shitsu’

Genki Takahashi

raised in Hiroshima, Genki decided to dedicate his life to tea at age 20 after returning overseas to reflect on his Japanese heritage

“the peace I felt sitting in the temple and chashitsu was different – tea for me is the Japanese soul”

inspired by its long history, Genki started working to revive traditional methods for growing, brewing, and serving tea

starting from a small farm in a countryside town, he has since opened three tea stands

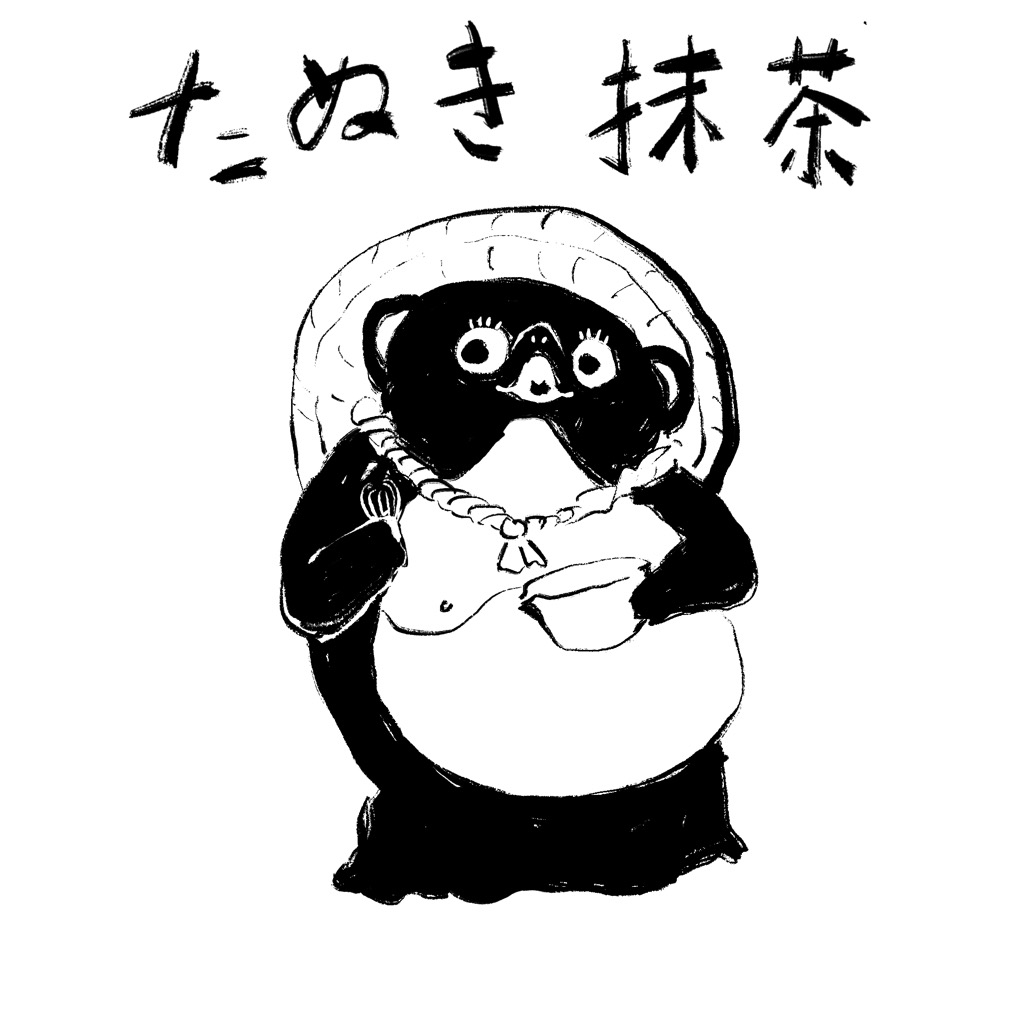

tanuki matcha (25g)

rewriting matcha

matcha has spread rapidly in the last few years, straining farmers in its production. understanding this issue first requires understanding matcha’s complex history and how we unknowingly perpetrate classicism today

we would be grateful if you could take a minute to read more

the tea ceremony

the Japanese tea ceremony, chado, started as a way to practice a path to enlightenment. the master Sen no Rikyū’s perfection of tea created the intricate ceremony that has largely stayed the same for hundreds of years.

chado slowly turned into a powerful tool, one that was offered as a gift to forge alliances among the upper classes. tea was pushed aside, and the ceremony was more about etiquette and a peace offering in a politically cutthroat environment.

because two types of matcha, ‘powdered tea’, are prepared in the ceremony, it became a drink that came to represent the elite. most Japanese people would go their whole lives without drinking matcha or experiencing any kind of tea ceremony

the first tea master

Sen no Rikyū grew up the son of a wealthy fisherman in Sakai, a port city where the merchants were rich enough to have great social standing and influence. he began to study tea under Takeno Joo at a time when the tea ceremony was entrenched in politics and diplomacy, being lavish and very high class. the current daimyo, a powerful lord, of the time even prohibited the ceremony’s use for anyone other than his closest allies.

Rikyū did not agree with the lavish ceremony and its political motives. He eventually entered service to a new daimyo, Hideyoshi, and constructed a simple wabi hut for serving tea. Rikyū would go on to establish the utensils, procedure, and etiquette of the modern Japanese tea ceremony. He preferred pottery made from ethnic Korean potter Raku, who created uneven rice bowls that Rikyu adopted as the first pieces for the tea ceremony.

Although Rikyū had been one of Hideyoshi’s closest confidants, because of crucial differences of opinion and because he was too independent, Hideyoshi ordered him to commit ritual suicide called seppuku. his last act was to hold a tea ceremony

Rikyu’s great grandson had three children that each established the three modern schools of the ceremony called Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushakōjisenke.

wabi-sabi poems

Casting wide my gaze,

Neither flowers

Nor scarlet leaves:

A bayside hovel of reeds

In the autumn dusk

Show them who wait

Only for flowers

There in the mountain villages:

Grass peeks through the snow,

And with it, spring.

the modern envionment

matcha’s bright green color comes from tea leaves, called tencha, being grown in the shade for a few weeks. but the tea plant requires partial sun to grow well, making it difficult to consistently keep the plants alive

to make matcha on the scale it is demanded at today, addition of fertilizer and pesticides became necessary.

this also meant that small farmers could not outcompete large companies, despite how high quality and organically produced their tea was. many large companies today have provided subsidies for farmers to stop growing it and bought up land and production facilities

matcha’s popularity today has only furthered its perpetration of social inequality.

Tanuki Matcha

everything has a spirit in Japanese folklore, whether it be an animal, rock, or even a cooking pot. these spirits are known as yōkai and are still very present in daily life in japan.

its important to keep in mind that the concept of yōkai has evolved greatly between regions and over time. but in general, the feeling that life is interconnected is incredibly strong and the idea that all actions matter.

what is tanuki?

Tanuki is one such yōkai, one of the most prevalent in modern Japan.

said to live in the mountains and forests throughout japan, these ‘raccoon dogs’ possess powerful magic, with the ability to change shape into anything

just like humans, every tanuki spirit is very different. some tanuki have been known to be extremely intelligent, adopting human names and playing tricks. others are generous and love the company of humans, bringing them prosperity.

this has made tanuki an icon of daily life. statues of it are commonly found in front of homes

thank you to Genki, Kyoko, and all the people that taught us about tea in Japan

while matcha has become so much more widely recognized and led to appreciation for japanese teas, we feel that much of its story has been misrepresented today. by taking these few minutes to read, you have done so much help out many farmers and families around japan.

genmaicha

the ‘people’s tea’

beginning in Kyoto during the 20th century, economic hardship drove up the price of tea leaves. merchants began to add roasted brown rice, which was readily accessible to farmers, in order to stretch supply. genmaicha, meaning ‘brown rice tea’, was created. it was affordable to almost everyone, with street vendors selling by the cup throughout the year.

mottainai

buddhist traditions in japan teach that all things are interconnected. this means that to waste something is to diminish its value, a principle known as mottainai.

the practice of adding leftover rice to genmaicha reflects this, giving back to both the people and honoring the harvest.

inari Ōkami and kitsune

japanese kami are the deities embodying the souls present in all things.

inari, translating directly to ‘rice bearer’, is known for bringing wordly success through rice, fertility, foxes, sake and agriculture. her messengers are kitsune, pure white foxes that are especially associated with the rice harvest.

the rice harvest is one of the most important events of the year. the fall season is always easily recognizable in art because of the characteristic yellow color of the rice grasses just before the harvest.

what does adding rice do to tea?

genmaicha was very common during times of famine and scarcity not only because it was a way to make tea more affordable. with the starches and fiber present in brown rice, the tea helped to maintain energy levels and suppress appetite.

brown rice is also rich in water-soluble nutrients like magnesium, selenium, and manganese. these compounds are extracted into tea when the rice is soaked in hot water.

best consumed before or after a meal, the soluble fibers in rice will act as a prebiotic. slowing the absorption of carbohydrates, blood sugar is regulated and energy is released over a longer period of time.

sencha

reinventing japanese tea

baisaō

originally a zen buddhist monk, baisao left his monastery for kyoto. around 1735, he began to sell tea on a donation basis out of a woven basket lugged on a stick.

tossing tea leaves into a pot of boiling water, baisaō created a new kind of casual tea. wildly different from the rigid form of matcha’s preparation in sado, this ‘infused tea’ caught the eye of many monks and intellectuals for its humility.

being conscious of his growing fame, baisaō renounced his position as a monk and changed his name. this was to avoid the development of a ritualized sencha tradition mirroring what was done with matcha. as an expression of this, he burned many of his tea utensils shortly before dying.

genki’s seicha

today matcha has stolen the spotlight surrounding japanese teas. recognizing the strain put on many smaller tea businesses, genki wanted to create a new type of tea to bring the attention back to Baisao’s tradition.

back in the day, farmers used to have to carry freshly plucked tea leaves from field to factory. in this time, the leaves would start to slowly break down. this meant that traditional sencha was not bright green as we know it today, actually being slightly yellow with a mellow flavor.

genki sought to recreate this type of tea, allowing it to wither before steaming the leaves. with it, seicha, meaning ‘pure tea’ was born.

“if I could drink one tea every day for the rest of my life, it would be seicha” – Genki

tins + teas

‘roasted brown rice’

$30

25g

‘powdered’

$40

25g

‘barley’

$25

25g

original

$20

25g

original

$25

25g

original

$15

10g

hamacha

hamacha, or ‘sea tea’, was invented by my tea teacher named Genki Takahashi. starting in a small rice town called Sera, Genki started growing his own tea in the countryside and sharing it with people in Onomichi at his Tea Stand Gen

hamacha’s genesis

Onomichi is a seaside town brimming with artisians, tradition, and cats alike. famous for its seafood, the local fishermen have perfected their craft over generations.

one day, Genki observed the locals hanging freshly caught fish out to dry before cooking. upon asking, the fisherman responded that drying them in the sea breeze for five days concentrates the sweetness and flavor of the fish best.

the idea for hamacha was born, and Genki spent three years of harvests experimenting with how to dry freshly plucked zairai tea leaves by the seaside

honestly my first time drinking this tea, I didn’t think it was made from the tea plant. the flavor was indescribable